In recent years, western economies have enjoyed incredibly low levels of price inflation overall. Certain costs have bucked the trend, however, as you will know very well if you have tried renting an apartment in London or San Francisco. Another of these “outliers” appears to be the cost of repairing aircraft hull damage. So, how big is the problem and what are its causes?

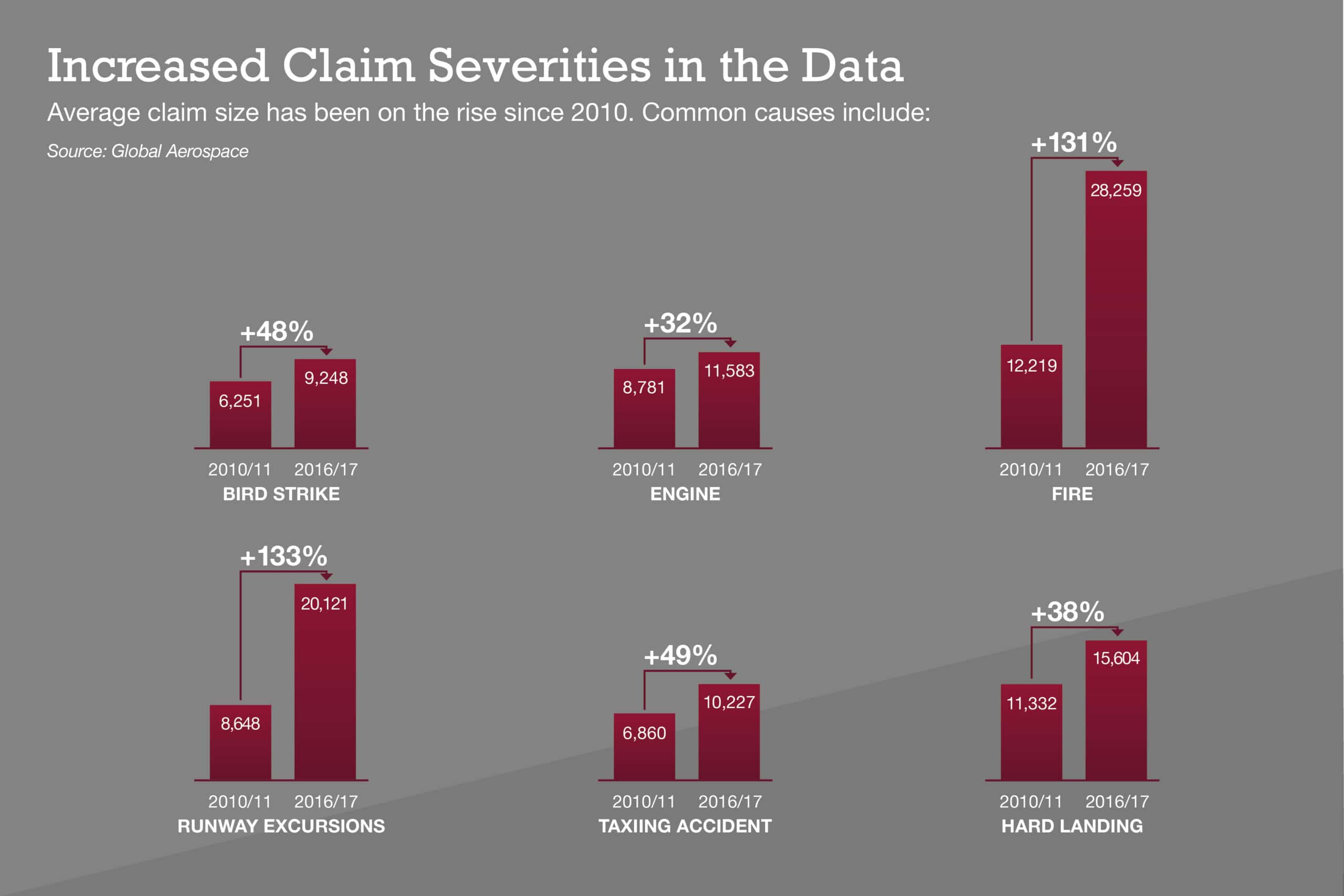

Earlier this year, Global’s actuaries looked at the cost of larger partial hull losses from our airline portfolio over a six-year period (2010/11 to 2016/17). They found that for all loss causes (e.g., bird strike, runway excursion, taxiing incidents), the average size of the claims rose between 32% and 133% depending on the type of loss. By way of comparison, the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by about 10% in the same period.

Understanding Repair Cost Increases

This trend is just as apparent in our general aviation business. To understand the reasons behind it, it is necessary to look at the way aircraft and components are manufactured today and the way in which practices in the industry have changed.

For older aircraft, the issue is often the availability of spare parts because manufacturers today keep very little parts inventory on hand. This means a replacement part may have to be remanufactured at very high cost. Additionally, the availability of certified refurbished parts has become much more limited as many manufacturers are reluctant to accept repairable damaged parts in exchange for discounted new parts.

On modern aircraft, however, the biggest factor pushing up costs is technological progress. Most people are aware that repairs to components made from composite materials can be much more complex and expensive than was the case for those made from traditional materials like aluminum. In fact, where the damage requires special tooling or proprietary bonding techniques, there may be no option available for repair other than to contract with the OEM. As an example, a wing tip repair on a “classic” metal airliner would not typically exceed USD50,000. The same repair on the latest carbon fibre wing tips can easily cost USD1.5 million.

Composites, of course, have brought significant weight, performance and efficiency gains, and their use in fuselage parts and control surfaces is increasingly becoming the norm. Fundamental changes in the design and manufacturing of power plants have also driven impressive performance improvements, but with the downside of increased repair costs.

For a start, newer engines are being built to tighter tolerances, which means that it takes less damage to cause an internal component to fall beyond the repairable limits set by manufacturers. In older designs, this might have meant replacing a disc from the compressor, for example. But in many newer engines, compressors are cast as a single unit, which means that the entire unit has to be replaced even if the damage is only in one stage. In some of the latest jet engines, even the fan set is made as a single unit, which means that replacing one or two fan blades following a bird strike is no longer an option.

Prevention Beats Cure

For insurers, this inexorable rise in repair costs ultimately must be reflected in the premiums charged for hull coverage, the deductibles that apply or a combination of the two. On the other hand, for aircraft operators, FBOs and ground handlers, investment in loss prevention measures increasingly looks like money well spent, whether in training and awareness initiatives or in the purchase of technology such as proximity sensors on ground service vehicles. At the end of the day, prevention beats cure any way you look at it.